Often books are published in an imperfect state. The first print run may include minor grammar errors or other issues that a publisher fixes in subsequent printings. But what happens when someone decides that larger changes are necessary?

In publishing, the term “edition” can indicate several different types of alterations to the original manuscripts. Translations can count as different editions as can international versions that may have different formatting or cover requirements. But books with extensive textual or plot revisions fall into an altogether different category. Producing this last type of editions often involves large changes in society or in the consciousness of the author.

Because these major alterations occur for vastly different reasons, I’m highlighting a few of the most interesting cases below.

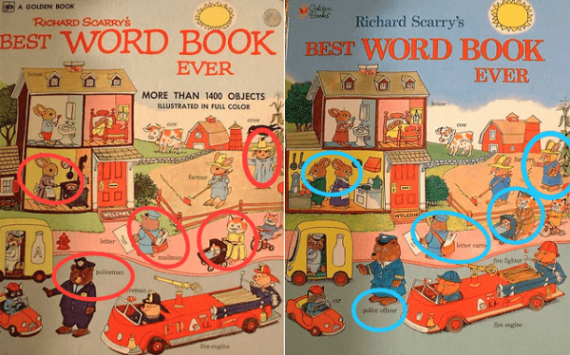

Richard Scarry, The Best Word Book Ever

Scarry’s children’s books feature simple stories filled with anthropomorphized animals. Though Scarry first began publishing in 1949, he has continued to update his over 300 stories in order to reflect changes in American society. Alan Taylor from The Atlantic noticed several of these differences in Scarry’s The Best Word Book Ever. Some changes were simply alterations to language uses. “He comes promptly when he is called to breakfast” was changed to “He goes to the kitchen to eat his breakfast” for example. Other changes result in more equitable gender roles. In a 1963 edition of the book, a male bear drives some type of construction or farm equipment, but in the 1991 version, a female bear is driving the same implement. Scarry and his publishers ultimately made the changes so that the book would continue to be relevant to modern readers and reflect their lived experiences.

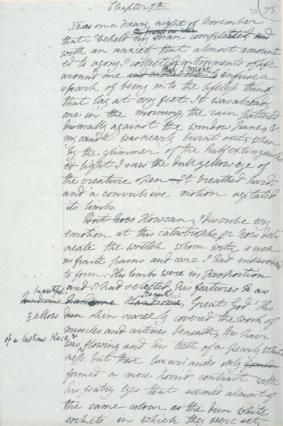

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

Though most people are acquainted with the story of Frankenstein, they may not know that they are likely familiar with the second rather than first edition of the tale. Shelley first published Frankenstein in 1818. The original story featured the fall of a great family, hints of incest, different characters, and a more thorough reflection of life at the time of the book’s writing. In 1831, Shelley published a new version of the work that removed some of the rough narrative edges (and the incest). The 1831 edition is the one that has gained the most renown. If you are interested in learning more, check out John Harcourt from Ithaca College’s analysis of the subject. It is a quick and enlightening read.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit

In its original 1937 incarnation, The Hobbit did not necessarily fit well with the Lord of the Rings trilogy, which makes sense; Tolkien had not fully conceived of the trilogy back then. By the mid-1940’s though, Tolkien wanted to ensure that the books made sense when read together. In order to make them more narratively cohesive, he sent a revised version of The Hobbit to Allen & Unwin, his publisher, to see if they wanted to create a new edition to the work. Ultimately they did produce a revised version in 1951. This second edition focused more on Bilbo’s interactions with Gollum and emphasized the lure of the ring. Minor changes to the text also occurred in 1966 and 1978, creating third and fourth editions respectively. Today over 50 versions of The Hobbit have been published though the vast majority of these are simply international or translated versions that reflect the 1978 textual changes.

— — —

Making major changes to texts happens with remarkable frequency. Historically, the changes have only occurred if the author has made an egregious error, or if alterations make sense with subsequent print runs. In this era of print on demand books, however, authors and publishers have more flexibility in terms of manuscript changes; they no longer have to wait until 500 first run books have been sold or lose money before integrating the changes. Even self-publishers can overhaul their manuscripts after publication by simple uploading new files to their vendor sites though companies like Amazon do encourage authors to indicate that these changes have created a second edition of the work. (People in publishing are sticklers for tracking changes like that.)

Whether the creation of new editions results from changes in society or narrative needs, I love exploring how and why authors redevelop their works after the initial publication. When I read, I think of books as fairly static though in reality, their narratives have the potential to change quite a bit. I’m interested to hear if you all know of other major changes to manuscripts or if you have had to change your own manuscript after publication. It is such an unusual system that I can’t help but want to know more.

— — —

Image Attributions:

Alan Taylor, Richard Scarry’s The Best Word Book Ever, Flickr, 25 October 2016.

Mary Shelley, Manuscript Page from Frankenstein, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, London, 1816.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit, Allen & Unwin, 1937.

This is so fascinating! I always once it’s done it’s done and there’s no changing anything anymore! I wonder if I can find a copy of the first version of Frankenstein.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I bet a first edition is floating around somewhere! Some industrious soul may even have digitized it. (Which is the dream.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is so the dream. I’ll have to search

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a first edition!!! Loved it. Love it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

…first edition of Scarry’s book that is. And I teach The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have such a fondness for Scarry’s books. I’m sure it’s partially nostalgia, but they are wonderful books for kids.

And teaching Tolkien sounds like a great way to engage students!

LikeLike

My sister and I once imagined entering Scarry’s world, living with the “animals.” Now, I dream about living in Middle Earth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog.

LikeLike

Fascinating! Thank you for this enlightening post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed it! I’m always happy to share these things.

LikeLike

Amazon told me I can make up to 10% changes to my book and keep it as a first edition. The problem with going to the second edition was the very possible loss of all the reviews. We wanted to re-format the pages in my first book, but this took it over the top and I couldn’t face losing over 60 reviews it took a long time to get them!

LikeLiked by 2 people

The loss of reviews is definitely a concern in the digital era! It’s too bad that you couldn’t do the reformatting though. I’m sure that was frustrating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes wanted to make it look more reader friendly, but it’s too late now 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Archer's Aim and commented:

This is an interesting look at editions of books and why they get changed. This certainly lends to the idea of making updates to books as necessary today when it’s far easier to accomplish with technology. Reader experience is paramount to consider when considering these changes regardless. Will a new edition make the book better or drastically change the whole story?

LikeLiked by 1 person

So interesting to read the “Why” behind the classic, 2nd Editions you mention. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed it! It’s so fun to hear about these stories.

LikeLike

Fascinating, Kristen! Makes me want to read and learn more about them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. I had NO idea! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some books have such interesting histories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just one of the reasons reading is so awesome… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great article about a really fascinating subject, Kristen – I’m guessing that this is going to be an ongoing and increasing practice now that we can make changes to ebooks with the click of a button…

LikeLiked by 1 person

No doubt! It is so tempting for authors to keep tweaking works these days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And of course – I think it’s sometimes necessary… In the case of Tolkien I reckon his instincts were right to iron out the anomalies between The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely!

LikeLike

It’s great to be able to correct errors easily, but a possible downside is never being finished with a book. At some point an author has to say “It is what it is,” and move on to new projects.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree. It can be so easy to get bogged down in the details, but sometimes you just have to let a work rest. And honestly considering how horrified I have been by some of my old works, I can’t imagine wanting to go back and edit them again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on The Vanishing Writer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that. I have a second edition WIP and I wanted to enable buyers of the original to update their own free of charge, so I resisted giving it a whole new title as one editor suggested. Only the beginning is substantially different, after all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s gracious of you to offer the free update! I’m sure your readers will appreciate that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had a hard time getting my publisher to fix typos and make a few wanted changes, Kristen. It was one of my reasons for switching to indie. From reading this, I’m relieved to find that my request wasn’t out of the ordinary. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sorry they made it difficult! I know that if books have already been printed in decent quantities, some folks are leery of making changes. Still, it sound like you’ve gotten a happy ending with indie publishing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How very interesting! I do believe Shelley published yet another edition of Frankenstein between the two you mention (in 1823). Just want to add (for MyBookJacket) that the copy of the book I have now (an 1831 third edition) has all the 1818 material collated in an appendix. It’s a Penguin Classics publication updated 2003.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perfect! Thanks for sharing that information. You’ve certainly made it easier to track down.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Kim's Author Support Blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is fascinating. I knew present-day authors could make changes to their books and am thinking of doing so myself to tie in my first book (that I had no idea would become part of a series when I started) with subsequent books a little more tightly!

But I had no idea that some ‘classic’ books have been changed so many times. My children loved the Richard Scarry books especially one called (I think) What Do People Do? – about different ‘grown up’ occupations. I was thinking of buying this book for my grandson this Christmas if it is still in print, and will now be interested to see if there have been changes. There certainly have been in the real world.

Recently I bought another great favourite of my own children for another grandson – Flat Stanley by Jeff Brown. When it arrived in the post I flicked through with curiosity as I hadn’t read the book in many years. I was actually surpised how dated it was and had completely forgotten that there is referance to a ‘cigarette case’ amongst other things. I expect that wouldn’t have seemed odd to me twenty five or more years ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t thought about Flat Stanley in years! Now I’m going to have to track down my copy and see if I notice anything like your cigarette case example.

Are you thinking of making the book changes for the Berriwood series or something else? Either way I love that you are thinking about how to make your works consistent. Writing a series intimidates me a bit for precisely that reason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it’s on the Berriwood series. The Palaver Tree started off firmly as a stand alone. The story takes place in a Cornish village but also far away in Africa. It was only when I had finished that first book that I started to think of other, supporting characters in the village and what might happen to them! I’m now writing the third book and, although each story is quite separate there are continuing threads and references about the village and, I think, before I go any further I should make sure everything stays consistent. I don’t anticipate huge changes but I will check with regard to Lucinda’s comment re the 10% rule. This is something to bear in mind as reviews are so precious.

Check out Flat Stanley – it surprised me!

LikeLike

Huh. I had no idea this was such a big thing. Though, I’m kind of glad it is because I can’t honestly recall the number of books I’ve read where there were errors. Some are minor spelling errors, but some are actual inconsistencies in the narrative, and it drives me up the wall because it’s a published piece of work. It should have been proof-read a hundred times. What’s more, it makes me nervous about what errors will be left in my manuscripts should they ever be published.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a relief to know that the option exists! (Though once I’ve finished a piece, I do like to leave it ‘finished’. Otherwise, there is too much of a chance that I’ll spend the rest of my life worrying about a single book.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh man! I can imagine. If I were ever to be published and I saw a mistake in a printed copy, I’d probably just freak out and demand a retraction of all the books. :p

LikeLiked by 1 person

No kidding!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on The Owl Lady.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had no idea – so interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really is fascinating how much some books change over time!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kristen, I am relieved that I found your blog changing publications. Independently, I published and released my first book June of 2016. After the initial release, I did another read through and found a few typographical errors and page formatting revisions I wanted to make on a few pages – nothing drastic. I was stressing over it until I came across your blog. Thanks for letting me know it is okay…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad that it was helpful! There is something uniquely horrifying about publishing a book and then spotting errors in it.

And congratulations on your almost-first anniversary of your book. That is a big milestone!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I feel like a mother wanting to celebrate, but don’t know exactly how!

LikeLiked by 1 person